also

at: http://www.blueberry-brain.org/winterchaos/RoulettiInChina.htm

Commentary: Operational Definitions: Triage and Social Significance

By:

Frederick

David Abraham, Director, Blueberry Brain Institute (USA) and Occasionally

Visiting Professor, Silliman University (Philippines): Research in psychology,

brain & behavior, systems theory, and interests in philosophical

hermeneutics, postmodernism, scientific and social philosophy, cosmology,

epistemology, history, skiing, kayaking, and jazz. (see www.blueberry-brain.org).

The

following comments are also mirrored at:

http://impleximundi.com/tiki-read_article.php?articleId=17#comments

1.

Prefatory Comment: Roulette has asked me to

critique in an effort to sharpen his essay, to which I humbly and reluctantly

submit despite a lack of qualifications. Nonetheless, while its virtues are

abundant and self-evident and need no comment from me, in an effort to satisfy

his request, I focus on two related issues that concern me. The first deals

with the difficulty of providing operational definitions for “common sense” and

many of the other terms used, and the second deals with the potential social

significance of his definition of “common sense”.

First Issue: Operational Definitions:

Difficulty for “Common Sense”?

2.

Before

turning to Roulette’s definition, perhaps I could briefly review some uses of

the concept of “common sense” (based and quoted from Wikipedia).

(a) Various sense information is integrated into a perceptual

experience (Aristotle, Ibn Sina, and Locke).

(b) Thomas Reid, founder of the Scottish School of Common Sense, in Inquiry

and in Intellectual Powers, states ‘principles of common sense are

believed universally’. He borrowed the term “sensus communis” from

Cicero, a Latin term that Roulette could add to his dictionary of linguistic

synonyms; this use is a condition of Roulette’s definition of “common sense”.)

Reid was trying to establish a grounding for rational action, and thus was on a

program similar to Roulette’s, although with a concern for philosophy more than

everyday action.

|

|

Thomas Reid From http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/reid/ Courtesy (there) of the |

(c) As a fault rather than a

virtue. E.g., Einstein, “Common sense is the collection of prejudices acquired

by age eighteen.”

(d) As a virtue rather than a

fault, by designating rationality, reason, logic, and common agreement as a

basis for designating a correct choice of action. (Similar to b, and pretty

much equivalent to being an implication of Roulette’s definition.)

(e) Thomas Paine’s arguments against British rule in his pamphlet Common

Sense.

3.

For

the first use, I quote the ideas of the Islamic scholar, Abu ‘Ali al-Husayn ibn

Sina (aka Avicenna), on the rational self as presented by Rizvi (2006).

“This

rational self possesses faculties or senses in a theory that begins with

Aristotle and develops through Neoplatonism. The first sense is common sense (al-hiss

al-mushtarak) which fuses information from the physical senses into an

epistemic object. The second sense is imagination (al-khayal) which

processes the image of the perceived epistemic object. The third sense is the imaginative

faculty (al-mutakhayyila) which combines images in memory, separates

them and produces new images. The fourth sense is estimation or prehension (wahm)

that translates the perceived image into its significance. The classic example

for this innovative sense is that of the sheep perceiving the wolf and

understanding the implicit danger. The final sense is where the ideas produced

are stored and analyzed and ascribed meanings based upon the production of the

imaginative faculty and estimation. Different faculties do not compromise the

singular integrity of the rational soul. They merely provide an explanation for

the process of intellection.”

|

|

|

Ibn Sina, and the Canon of Medicine (al-Qanun fi’l-Tibb). |

Note that his first sense is used in the Aristotelian-Lockian sense of

3-a above, and is quoted here in part because it gives Roulette another

language (Arabian I presume as most of Ibn Sina’s writing was in Arabic, a few

in Farsi) for his dictionary of ‘common sense’ language equivalents. The

remainder could be considered as parts of the psychological processes that lead

to an act that Roulette might consider as possessing “common sense” or the lack

thereof. At any rate, Avicenna deserves more attention from us, and from having

an interest in the 11th Century scholar, Bernardis Silvestris, I

know that he had a great impact on the transformation of High Medieval scholarship

(which I consider essentially the beginning of the Enlightenment; it included

Roger Bacon, one of the originators of modern empiricism. Abraham, 2001).

4.

Turning

now to the first concern I have with Roulette’s essay, that of operational

definitions, I note that it is mentioned in Stanley Krippner’s commentary [C2]:

"Now what you need is an operational definition of common sense. {cf. 84,

89} To start, couldn't you say that "common sense" is the ability to

make decisions (that are functional for the individual as well as for his/her

social group) based on experience and past learning?"

5.

Since

I concur with this need for operational definitions, I might mention some

proposals for criteria for a definition of ‘operational definition’.

(a) Percy Bridgman (1928): “. . . in general, we mean by any concept

nothing more than a set of operations; the concept is synonymous with the

corresponding set of operations.”

(b) Smitty Stevens (1939): “1.

Science, as we find it, is a set of empirical propositions agreed upon by members

of society.” 2. Only those propositions based upon operations which are public

and repeatable are admitted to the body of science. 5. A term denotes something

only when there are concrete criteria for its applicability, and a proposition

has empirical meaning only when the criteria of its truth or falsity consist of

concrete operations which can be performed upon demand.” (#s 3,4,6,&7

omitted here.) Note that these imply repeatability, reliability and validity.

(c) Wikipedia: “An operational

definition is a showing of something — such as a variable, term, or object

— in terms of the specific process or set of validation tests used to determine

its presence and quantity. Properties described in this manner must be publicly

accessible so that persons other than the definer can independently measure or

test for them at will. An operational definition is generally designed to model

a conceptual definition. The most basic operational definition is a process for

identification of an object by distinguishing it from its background of

empirical experience.” I quote this because “common sense” involves, with which

Roulette starts his essay, conscious experience, within which “common sense” is

embedded. There are ways that psychologists have dealt with in objectifying

experience. Thus I add mention of some such treatments.

(d) W. Robinson: “In survey

research, the responder often must create and apply the operation if one is not

included in the question . . .” Besides questionnaires, one might add,

interviews, text analysis, qualitative research, action research, and so on.

These may produce results, which seem to meet the criteria of reliability, but

not necessarily of validity, i.e., the contents of conscious experience

(Roulette [1,2,3]).

6.

We

now turn to Roulette’s definition [7, footnote], and then Stanley’s comment

[C2] on the need for operational definitions.

Roulette:

“Lacking common sense, having no common sense, and aberrant common sense all

are terms referring to persons’ ways of thinking that differ from the ways of

thinking in their cultures, groups or herds. In other words, aberrant common sense

involves personalized styles of “sense” and “sense-making” which do not comport

with common heuristics, patterns, and styles of “sense” and “sense-making” used

by peers, within herds or other groups. Copyright © 2007 by Roulette William Smith, Ph.D. –

All rights reserved.”

Stanley: “Now what you need is

an operational definition of common sense. {cf. 84, 89} To start, couldn't you

say that "common sense" is the ability to make decisions (that are

functional for the individual as well as for his/her social group) based on experience

and past learning? [cf. 89]”

7.

Stanley

makes the important point in suggesting the need for an operational definition

of “common sense”, but I am not sure that treating the behaviors as

“functional” or not, just moves the difficulties for operational definitions

due to ambiguities involved onto the new word “functional” which is fraught

with very similar ambiguities. Those ambiguities involve not only specifying

what the conditions for classifying behaviors and experience might be, but also

on the need for a consensus. This is inherent in that the “experience and past

learning” are as he points out, dependent on both the “individual as well as

his/her social group”. Like “common sense” these may depend of shifting and

differing views of the behavior and the context in which the behavior occurs.

Also, there is difficulty in specifying the individual’s social group. The need

for hermeneutics remains.

8.

It

might be mentioned that many of the terms Roulette employs suffer from the same

difficulties (and some of circularity), such as awareness, belief

and (vs) reality, uknowing neediness, worried wellness,

and others, although some case may be made for “face validity”, a catch-all

phrase designed to escape operational definition.

9.

Now

let us imagine a typical operational definition for “common sense” as a

traditional personality psychologist might approach it. You make some kind of

demographic specification of the “social group” and specify the procedures for

selecting a sample from that group. Then you take some of Roulette’s cartoons,

or other examples of behavior, and then have the experimental participants rate

the behavior as to their degree of common sense. The least set of ratings would

be like a triage or 3-point Likert scale: lacking, possessing, or ambiguous or

non-definable in terms of common sense. First is the likelihood that the

uncertain category would likely be the most chosen for all except the most

contrived situations. Second, the situations would likely be so specific that

the results might be very limited as to generalizability. I see the experiment

as having reliability problems, that is, replicability with other situations,

behaviors, and groups of subjects. Also validity problems. Even if you have

replicability, will you be measuring “common sense”? You may mainly be

measuring common social conventions, and certainly very little of the

subjective experience that produces the behavior for either the ‘participants’,

or anyone faced with a behavioral issue that is possessing or lacking in common

sense.

10.

But

Stanley and I may be unjust in asking for scientific criteria of Roulette, who

is not making a case for a scientific basis for his thesis. If he develops a

body of thought which can help people avoid the kinds of pitfalls with which he

is concerned, as well as avoid the costs to individuals and societies from

behaving foolishly or dysfunctionally, especially for those with “unknowing

neediness” [4], “worried wellness” [5], or “aberrant scientific common sense”

[80].

11.

As

a final comment on this issue, his suggestion that common sense can be aberrant

in science may invoke some contradiction, for that would imply that scientific

paradigm shifts often involve thinking outside the box, outside the prevailing

views in a given area, and by Roulette’s definition, by not being part of the

scientific social norms, would be aberrant. This paradox is highlighted in the

Horgan-Susskind debate (2005) on the role of common sense in (or versus)

science. This paradox can be kind of an extension of the Einstein quote above,

and of the disparate views of [2 c&d above] and the Reid program for the

evolution of rationality [2 b above]. Of course, thinking outside the box has

provided the basis of positive social change in all cultural spheres, not just science

(West, 1953). “The semiotic [pre-oedipal, chora in Plato’s Timaeus

feminine, non-metric, non-symbolic] overflows its boundaries in those

‘privileged’ moments Kristeva specifies in her triad of subversive forces:

madness, holiness, and poetry.” [can be generalized to avant garde

writers and artists in general] (Sarup, 1993, p. 124.) Kristeva is saying that

these overflows can lead to constructive social bifurcations. This

consideration leads us to the probematique for some social implications.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

John Horgan |

Leonard Susskind |

Verena |

Julia Kristeva |

Plato |

Issue two: Social Implications

12.

This

is the question of whether identifying individuals as aberrant by social

consensus and forces opens doors to their personal liberation and development,

or whether any resulting social control over them limits their individual

liberties and development. The possibility of control and boundaries of

individual development exists despite Roulette’s emphasis on trying to liberate

those children having learning difficulties. [8, 9], an issue dramatized by the

writings of R. D. Laing (1966, 1967, 1969).

13.

This

quandary is emphasized by Roulette’s tendency to biologize the “aberrant”.

E.g., he introduced the term “psychoviruses” to possibly explain the

transmission of non-genetic information leading to the evolution and

development of aberrations in common sense and to other psychosocial disorders

or dysfunctions. [9, see also10, 25, 30, 41, 50, 53, 65, 71] Another example

might be “functional” strokes [78, 91, 92]. Again this point of view is in

contradistinction to those of Laing, and were the foundation of other issues in

the Sociobiological debate (Segerstråle, 2000; Wilson, ). Laing’s views

included that of ‘madness’ being functional from a certain point of view, and

non-biological in its genesis, and he viewed society as constraining individual

freedom, and he portrayed psychiatry as often playing a role in that

repression, a sort of panopticon (Bentham, 1785; Foucault, 1977; Laing, 1967).

|

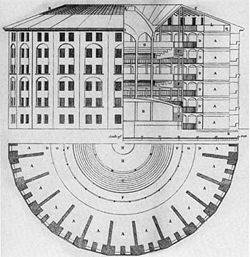

Blueprint of Bentham’s Panopticon (right). Such prisons exist today (below).

|

|

14.

“Foucault

inverts, following Nietzsche, the common sense [my emphasis, for obvious

reasons] view of the relation between power and knowledge. Whereas we might

normally regard knowledge as providing us with power to do things that without

it we could not do, Foucault argues that knowledge is a power over others, the

power to define others. In his view, knowledge ceases to be a liberation and

becomes a mode of surveillance, regulation, discipline.” (Surap, 1993, p. 67.) Surap

also mentions the likeness of Foucault’s panopticon (term from Bentham’s

design for prison surveillance, 1787; see also, ‘Big Brother’ in Orwell, 1949)

to the omniscient Christian god, Freud’s ‘superego’, and “the computer

monitoring of individuals in advanced capitalism”, to which I add the USA

PATRIOT Act (2001).

Conclusions

15.

My

commentary has an apparently schizophrenic aspect. My first issue argues for

rationality in science by advocating adherence to operational principles, but

the second issue shares Foucault’s concern that knowledge and rationality,

which were assumed to liberate individuals, may actually be exercised to

control and limit individual liberties.

While the first is ‘conservative’ scientifically, the second is

‘liberal’ socially, but both points argue for caution, and thus both share a

compulsiveness for care in their respective spheres, and especially in care in

applying scientific principles to social issues. Finding the balance is the

key.

16.

The

problem is increased when specific, discrete biological factors are sought to

explain broad, ambiguous, or fuzzy categories of behavior, especially if they

are difficult to define operationally, and have implications for social

programs. Roulette may well be correct, but we might wish for very clear evidence

for biological components of behavior.

17.

When

dealing with complex systems, including complex social systems, attributing

causality is most difficult, and entails not only the enumeration of the many

variables involved, but also expressing their relationships (system of

differential equations and exploring the value of their coupling constants, or

their equivalent in terms of agent-based modeling and other discrete rules of

change and decision). Without exploring this obvious caveat, it is worth noting

well-studied aspects of social systems theory (Bausch, 2001; Habermas, 1987;

Leydesdorff, 1997; Luhman, 1995; Parsons, 1951.)

18.

None

of this is meant to detract from the value and promise of the brilliant program

upon which Roulette has embarked, and we wish him well in its pursuit. It is

merely to provide an arena of discourse to protect it from any pitfalls of

common sense in its pursuit. He is a friend for whom I have the greatest

admiration.

|

|

|

|

|

Jürgen Habermas |

Niklas Luhmann |

Loet Leydesdorff |

References

Abraham, F. D.

(2001). Topoi and Transformation. The Journal of Psychospiritual

Transformation. (also:

http://www.blueberry-brain.org/chaosophy/Topoi3.html)

Bausch, K.C. (2001). The emerging

consensus in social systems theory. New York: Kluwer/Plenum.

Bentham, J. (1787). Panopticon. http://cartome.org/panopticon2.htm

Bridgman, P.W. (1928). The logic of modern

physics. New York: Macmillan.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish.

London: Penguin.

Habermas, J. (1987). Excursus on Luhmann's

Appropriation of the Philosophy of the Subject through Systems Theory. Pp.

368-85 in: The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity: Twelve Lectures,

MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. [Der philosophische Diskurs der Moderne: zwölf

Vorlesungen. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a.M., 1985.]

Horgan, J. (2005). In defense of common

sense. In J. Brockman (Ed.), Edge: the third culture. [Editor's

Note: First published as an Op-Ed Page article in The New York Times on

August 12th]

http://www.edge.org/3rd_culture/horgan05/horgan05_index.html#susskind

Laing, R.D., Phillipson, H. and Lee, A.R.

(1966) Interpersonal Perception: A Theory and a Method of Research.

London: Tavistock.

Laing, R.D. (1967) The Politics of

Experience and the Bird of Paradise. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Laing, R.D. (1969) Self and Others.

(2nd ed.) London: Penguin Books.

See also: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ronald_David_Laing

Leydesdorff, L. (1997). The Non-linear

Dynamics of Sociological Reflections, International Sociology 12,

25-45.

Luhmann, N.

1995. Social Systems. California: Stanford University Press.

Orwell, G. (1949). Nineteen eighty-four.

London: Secker & Warburg.

Parsons, T. (1951). The Social System,

Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Reid, T. (1764). Inquiry into the Human

Mind on the Principles of Common Sense. Glasgow & London.

Reid, T. (1785). Essays on the Intellectual

Powers of Man.

Rizvi, Sajjad H. (2006). Avicenna/Ibn Sina

(CA. 980-1037). In J. Feiser & B.

Dowden (Eds.), The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://www.iep.utm.edu/a/avicenna.htm

Robinson, W. Operational Definitions. http://web.utk.edu/~wrobinso/540_lec_opdefs.html

Sarup, M. (1988, 1993). An introductory

guide to post-structuralism and postmodernism, 2nd ed., 1993.

Segerstråle, U. (2000). Defenders of the

truth: The sociobiology debate. Osford: Oxford.

Stevens, S.S. (1939). Psychology and the

science of science. Psychological Bulletin, 35, 221-263.

Susskind, L., McCarthy, J., Gilbert, D.,

Reiss, S., Provine, R., & Huber-Dyson, V. (2005). In defense of uncommon

sense. (& other essays and rejoinders to Horgan). In J. Brockman (Ed.), Edge:

the third culture. http://www.edge.org/3rd_culture/horgan05/horgan05_index.html#susskind

Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing

Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct

Terrorism (USA PATRIOT) Act of 2001 (Public Law

107-56).

West. H.F. (1953). Rebel Thought.

Boston: Beacon.

|

|

|

|

Roulette |

Fred |