A Transpersonal Approach to Helping Unknowingly

Needy and Worried Well Persons:

An Example of In Situ Diagnoses and Follow-Up in the Study of Common

Sense and

Aberrant Common Sense in Post-World War II Germany

Roulette William Smith, Ph.D.

Institute

for Postgraduate Interdisciplinary Studies

Palo Alto, CA 94306-0846 USA

E-Mail:

najms@postgraduate-interdisciplinary-studies.org

E-Mail: najms@humanized-technologies.com

Revised Version of a Presentation to the

4th International Conference on

Humanistic and Transpersonal Psychologies and Psychotherapies

Baiyun, Guangzhou (CHINA) – September 24th-26th,

2007

Abstract

[1]

Transpersonal psychology subsumes many areas, although issues pertaining to

‘consciousness’

remain a central theme underlying many studies and reports. Examples include

classic studies

of consciousness and altered states of consciousness, meditation and

mindfulness, shamanism

and mind-altering substances, spirituality, and personal transformations.

Significantly,

philosophers and neuroscientists now are making substantial inroads into the

biological and

molecular basis for consciousness.

[2]

Philosophy Professor David J. Chalmers suggests that the challenges of

consciousness should

be dichotomized into “easy problems,” on the one hand, and the “hard”

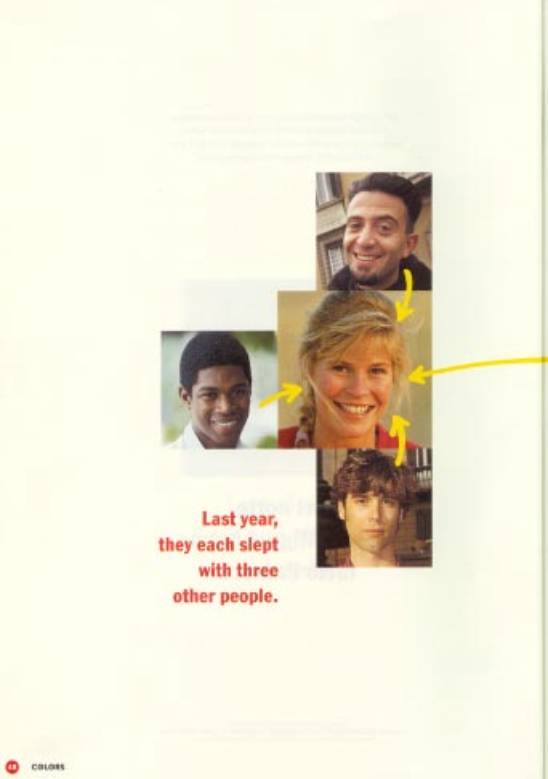

or “really hard problem,”

on the other hand (1995). According to Chalmers:

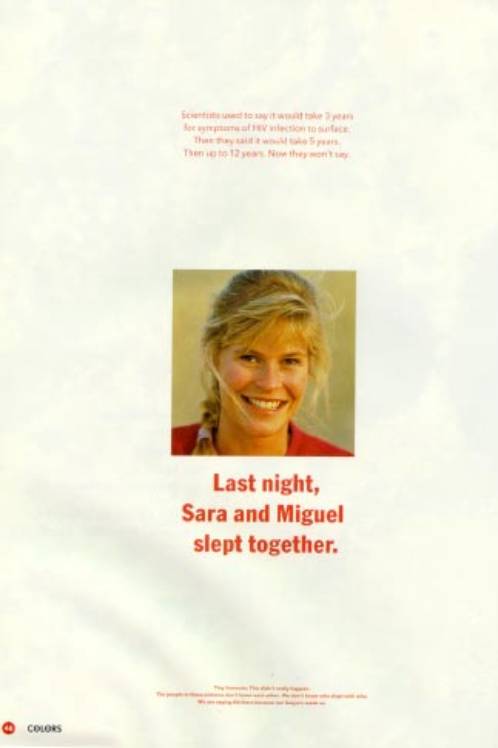

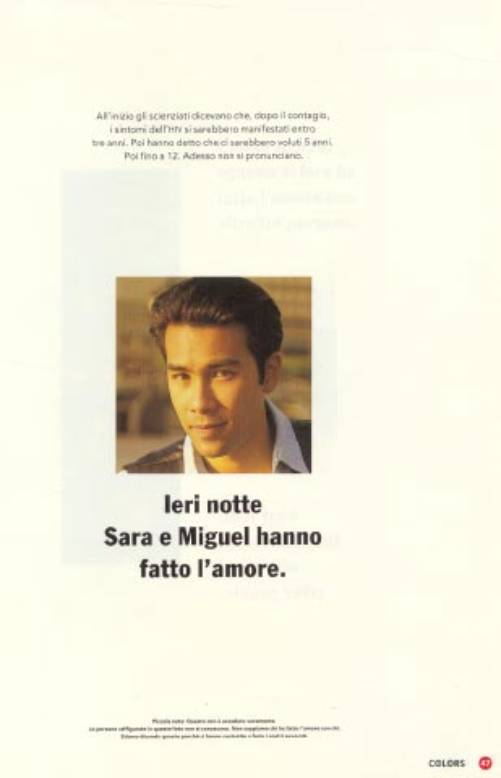

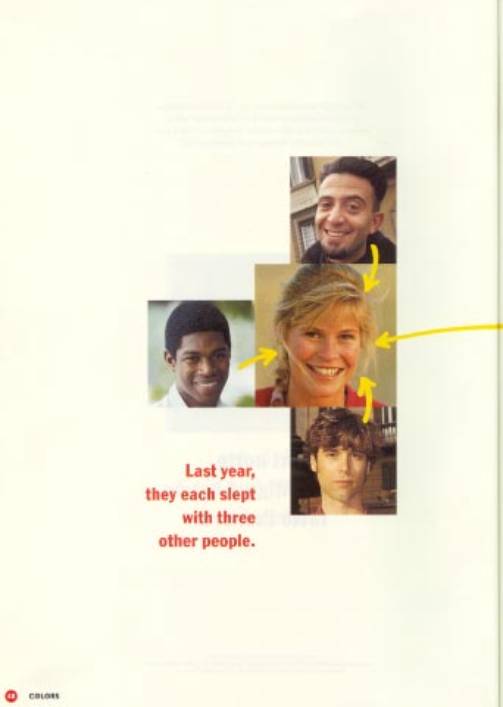

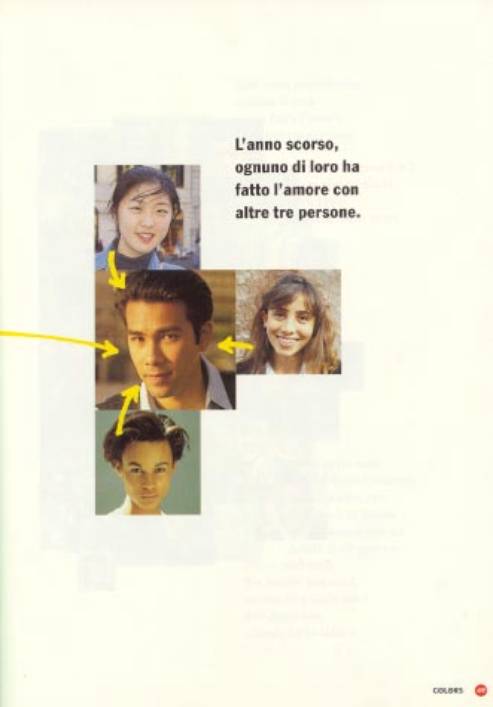

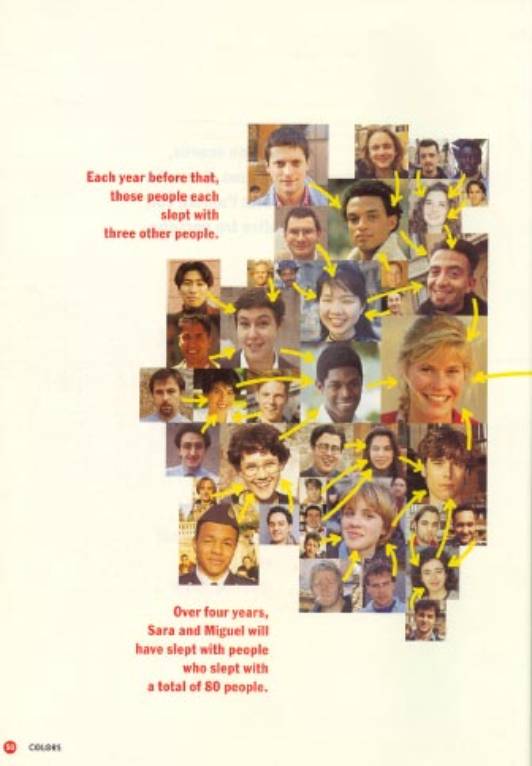

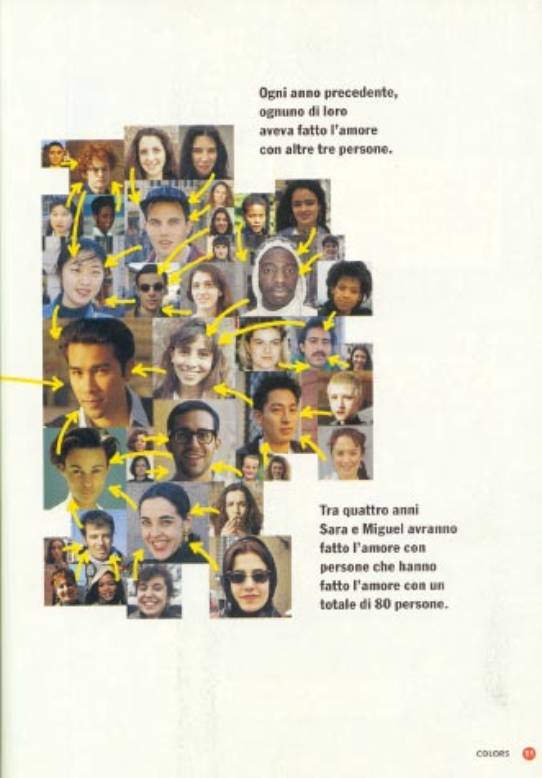

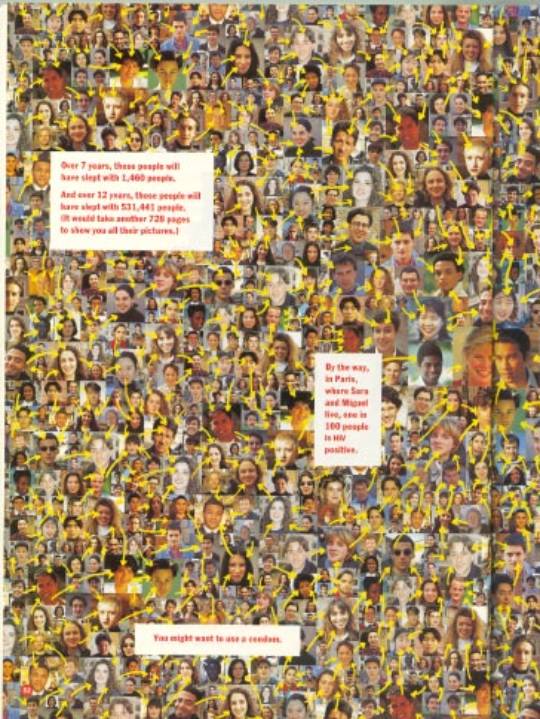

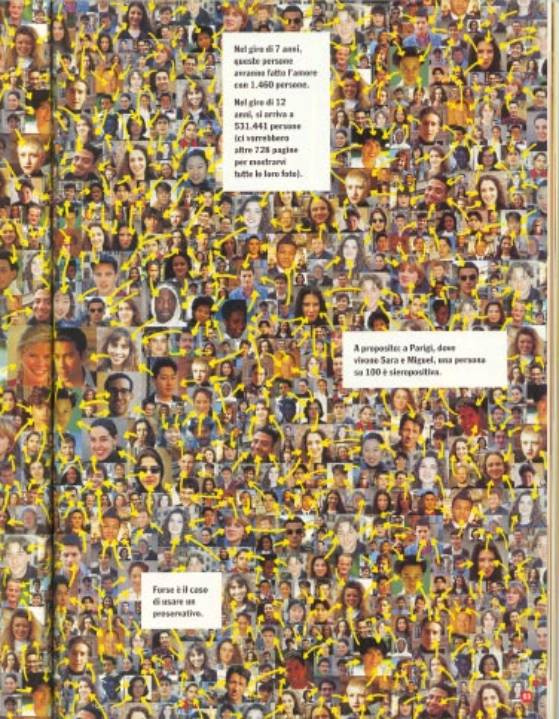

“The easy

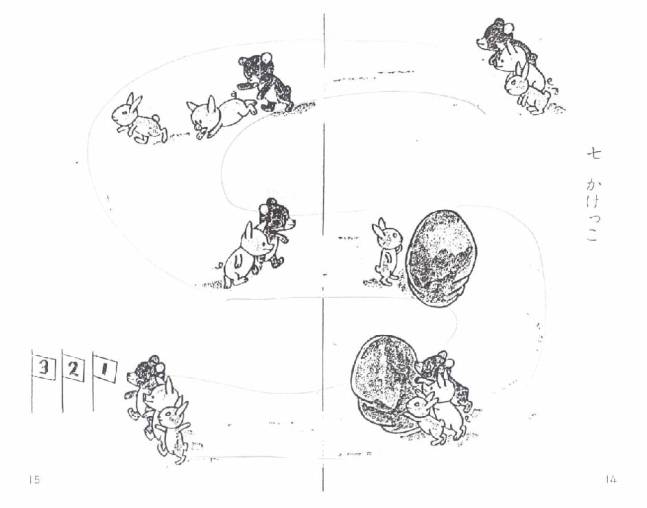

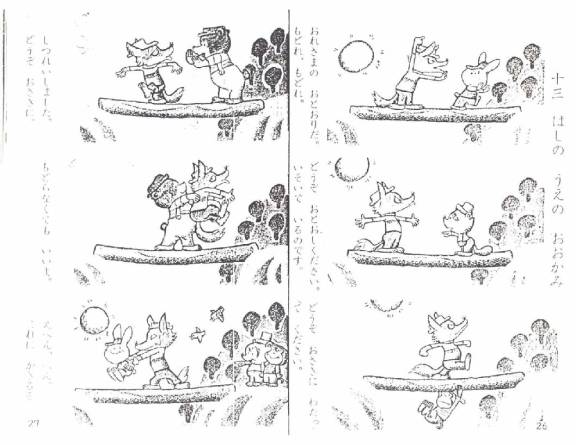

problems of consciousness are those that seem directly

susceptible to the standard methods of cognitive science, whereby a

phenomenon is explained in terms of computational or neural

mechanisms. … The easy problems of consciousness include

those of

explaining the following phenomena:

- the ability to discriminate, categorize, and

react to environmental

stimuli; - the integration of information by a cognitive

system;

- the reportability of mental states;

- the ability of a system to access its own

internal states;

- the focus of attention;

- the deliberate control of behavior;

- the difference between wakefulness and sleep.”

(p. 200-201)

Chalmers then states

that: “The really hard problem of consciousness is the problem of

experience. When we think and perceive, there is a whir of

information-processing, but there is also a subjective aspect. As Nagel (1974)

has put it, there is something it is like to be a conscious organism. This

subjective aspect is experience. When we see, for example, we experience visual

sensations: the felt quality of redness, the experience of dark and light, the

quality of depth in a visual field. Other experiences go along with perception

in different modalities: the sound of a clarinet, the smell of mothballs. Then

there are bodily

sensations, from

pains to orgasms; mental images that are conjured

up internally; the felt quality of emotion, and the experience of a

stream of conscious thought. What unites all of these states is that

there is something it is like to be in them. All of them are states of

experience.” (p. 201)

[3]

This report focuses on a third type of difficult problems; to wit, three

intriguing problems of

awareness, belief and reality. These problems

occasionally appear in clinical clients who

generally are not considered appropriate for research or laboratory

investigations of

consciousness. Their circumstances, challenges and problems ultimately may

prove to be far

more significant to researchers, especially if their realities, when

compared to their experiences,

contribute to the elucidation and explication of the onset and formation of beliefs.

[4]

One type of problem associated with reality is identified in persons who need

help or assistance,

and yet those persons have absolutely no knowledge or cognitive understanding

of their needs

for assistance. There can be no mistake that these persons possess

consciousness. Nor is

there any doubt that they possess personal senses of realities. Yet they often

misunderstand

more than they understand. They make mistakes and break things. They would

rather replace a

broken item rather than repair it. Their problems are classified under the

rubric of “unknowing

neediness.”

[5]

The second type of problem is identified in persons who constantly seek help or

assistance, and

yet they have absolutely no need for assistance. These persons consume enormous

quantities

of attention needlessly. Their behaviors are costly and chaotic. Their problems

are associated

with “worried wellness.” The worried well also misunderstand more than

they understand on

occasions. Interestingly, their problems often are relegated to third-party

insurance providers

that decide whether or not to pay claims. In the end, neither these persons,

their professional

healthcare providers, nor others are well-served by an underlying dysfunctional

healthcare

system unresponsive to fundamental needs.

[6]

The third type of problem perhaps is even more important at a practical level.

The underlying

clinical challenges point to issues of awareness – apart from

beliefs, experiences and realities –

in scholars, clinicians and potential clients. In other words, Chalmers’ really

hard problem

overlooks a transpersonal meta-issue of awareness in clinicians,

scientists, and, their subjects

and co-researchers. This meta-issue occasionally is manifested in ‘experimenter

effects’,

experimental bias, poor experimental design, and, failures in logic and “scientific

(and scholarly)

‘common sense’” (Smith, 1983; Smith, 2006b; Smith, in preparation).

[7]

Although differences in reality and perceived experiences may be

minor or subtle in most

persons, those differences may be quite profound in both the unknowingly needy

and worried

well. This report focuses on a specific subgroup of persons who are unknowingly

needy and/or

worried well. In particular, the focus is on persons who do not have

‘common sense’,1 and rarely

1 Lacking common sense,

having no common sense, and aberrant common sense all are terms referring to

persons’ ways of thinking that differ from the ways of thinking in their

cultures, groups or herds. In other words, Copyright © 2007 by Roulette William

Smith, Ph.D. – All rights reserved.

seek clinical

support. Attention is directed to the extremely hard problem of

consciousness involving:

- determining reality;

- disambiguating reality from experience;

- explicating belief formation in individuals and

herds; and,

- formulating clinical approaches and refining

methods associated with identifying,

documenting and

treating unknowing neediness and worried wellness. Persons who do not have

“common sense” occasionally may not understand, may misunderstand,

cannot understand, or may be out of touch with their

consciousness and/or realities.

[8] Why focus on

common sense and the lack of common sense? The present studies of common sense

date back to the 1970s and 1980s. During the 1970s, Smith (1971) flirted with

artificial intelligence aspects of common sense.2 Then, quite

fortuitously in 1985, 9 young elementary school students were observed who did

not have “common sense.” This determination was based on their responses to

mathematics questions and problems, and other aberrant personal behaviors. The

students were enrolled in grades 3 to 6 in a Sunnyvale, California (USA)

elementary school Mathematics Laboratory. The mathematics laboratory provided

remedial support for students performing poorly on mathematics tasks, and

provided enrichment tasks and activities for “gifted” students.

[9] The Mathematics

Laboratory was located in one section of the School Library. In a fortuitous

conversation with the school librarian, she revealed that those same 9 students

also performed poorly on reading tasks. These observations were reported to the

school principal who then recommended that these matters be discussed in

parent-teacher conferences. Those parent-teacher conferences revealed that for

each of those 9 students, one or both parents were uniformly “negative.” Those

parents simply did not (and possibly could not) say anything good, positive or

commendable about their child (Smith, 1986; Smith, 1987; Smith, 1988; cf.

Smith, 1971). After extensive historical and biographical research, the

phenomenon of “aberrant” common sense3 associated with parental

negativism was found to be widespread and universal, though not appreciated in

education, psychology, medicine, other social sciences, or any clinical

professions (Smith, 1992). The term “psychoviruses” then was introduced to

possibly explain the transmission of non-genetic information leading to the

evolution and development of aberrations in common sense and in other

psychosocial disorders or dysfunctions.

[10] Psychoviruses

are snippets of infectious, non-genetic information which interfere in

“normal” cognitive development. Those snippets of information indirectly may

lead to changes in DNA in brain. Psychovirus effects can be especially profound

in children between their births and approximately age six. Children appear to

be especially susceptible to adverse effects during the “terrible twos” and

shortly afterward. Situational effects also can produce psychoviruses and

those persons have

and use personalized styles of “sense” which do not comport with the common

styles of

“sense” used by peers, within herds or other groups.

2 This report does not review artificial intelligence issues

pertaining to common sense and consciousness. Rather,

the focus in this report is on “transpersonal” aspects of common sense in

humans.

3 Throughout this report we use “aberrant” to connote sufficiently

unusual manifestations of a phenomenon which

on the surface may appear usual or “normal.” Upon finer grained analyses – and

particularly in selected situations –

the underlying phenomena may be profoundly different, though not worthy of the

labels “abnormal” or “disabled.”

Copyright © 2007 by

Roulette William Smith, Ph.D. – All rights reserved.

psychoviral

responses (Smith, 1987; Smith, 1988; Smith, 1992; Reuters, 2006; Christakis and

Fowler, 2007). Although the concept of psychoviruses predates computer viruses,

the computer virus metaphor is appropriate. Psychoviruses differ from memes

(Dawkins, 1976) insofar as the gene–meme metaphor cannot explain many clinical,

laboratory or molecular findings which psychoviruses can explain. The gene–meme

metaphor also cannot explain evolutionary findings associated with a

“tripartite” model of evolution (Smith, 2005a; Smith, 2005b; Smith, 2006a;

Smith, 2006b; Smith, in preparation). Not insignificantly, the notion of

psychoviruses portends a potential companion notion of ‘psychovaccines’.

[11]

A possible molecular and evolutionary basis for common sense was investigated

during the past

three years (Smith, 2004a; Smith, 2004b; Smith, 2004c; Smith, 2007a; Smith,

2007b; Smith,

2007c). This includes studies of common sense in more than 41 cultures

worldwide (see Table

1; cf. Taormina, 2006).

[12]

As a microcosm, one component of the common sense research focuses on the

evolution and

development of common sense in post-World War II Germans, Jewish Holocaust

survivors

residing in the USA, and Jewish Holocaust survivors residing in Israel.4

These groups were

selected because much of World War II history and its consequences are amply

documented

and archived. Even if common sense in Germans and Jewish persons differed

before World

War II, one hypothetically5 should not expect statistically

significant differences among Jewish

Holocaust survivors in Israel and the USA. Thus, the underlying design provides

important,

though not-too-rigorous, controls in these exploratory studies.

[13]

Preliminary evidence suggests three divergent strands of common sense

associated with these

three subpopulations. War and other trauma also appear to contribute generally

to divergences

in common sense elsewhere6 – resulting from genocide,

ethnic-cleansing, other crimes against

humanity, and other specific traumatic events. A few examples include:

- Black Deaths in Europe produced different

behavioral responses and changes in Italy and other European countries

(cf. Tuchman, 1978; Boccaccio, 2000)7;

- Situations contributing to various diasporas

and internally displaced persons;

- Lynching African-Americans and others in the

USA in the late-1800s and early-1900s;

- The killing of large numbers of Armenians and

other persons in 1915 which began during the reign of Abdülhamid II – the

last Ottoman emperor;

- Traumatic aspects of World War I (particularly

in terms of social and military consequences) memorialized in many of

Wilfred Owen’s war poems8 (Owen, 1965);

4 Although Holocaust victims

included many persons and groups other than Jewish persons, the decision to

focus only on Jewish persons is based on practical considerations (e.g.,

availability of archives and documents, identifiable survivors and their

offspring, access, etc.). 5 This is a “null” hypothesis. In actual

fact, one should not be too surprised if there are significant divergences in

common sense in Jewish Holocaust survivors in Israel and the USA. Environment,

culture, government and other factors may contribute to those divergences. 6

In all instances of divergences in common sense cited in this report,

attributions of responsibilities or “blame” are avoided, even though blame and

causality may have relevance. Rather, the sole focus is on phenomena underlying

common sense, aberrant common sense, and changes in common sense. A goal is to

understand how evolutionary, molecular, developmental, situational and

clinical events may contribute to the explication of common sense and

changes in common sense. 7 Whereas Boccaccio’s writings were

diachronic, Tuchman’s approach was more synchronic.

Copyright © 2007 by

Roulette William Smith, Ph.D. – All rights reserved.

- The Holocaust during World War II;

- Relocation of Japanese-Americans to internment

sites during World War II;

- The Chinese Cultural Revolution between 1966

and 1976;

- Sectarian violence and ethno-political conflict

largely between Nationalists-Catholics and Unionists-Anglicans/Protestants

in Northern Ireland from the late-1960s to the late-1990s;

- The traumatic four year reign of the Khmer

Rouge in Cambodia (from 1975 to 1979) and its “killing fields” (cf. Cheam

and Gordon, 2007);

- Forced disappearances (that is,

"disappeared people" also called desaparecidos) and state

terrorism in Chile and Argentina during the 1970s and 1980s [also known as

Operation Condor (Spanish: Operación Cóndor, Portuguese: Operação

Condor)];

- The abduction, kidnapping and subsequent

criminal activities of Patricia (“Patty”) C. Hearst (granddaughter of

publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst) in 1974 by the Symbionese

Liberation Army (SLA);

- The war in Iraq (where Sunni, Shia and Kurdish

common senses are diverging);

- War veterans (returning from the Vietnam war,

the Gulf war, and the war in Iraq) suffering from post-traumatic stress

disorders (PTSD; cf. Milliken, Auchterlonie and Hoge, 2007);

- Genocide in Rwanda involving massacres of Tutsi

and Hutu subpopulations;

- Ethnic-cleansing in Bosnia-Herzegovina (among

Serbs, Croats and Muslims);

- Internal Palestinian strife in Israeli-occupied

Palestinian territories (among Fatah and Hamas factions);

- Trauma, rape and other sexual violence in the

Congo (cf. Gettleman, 2007);

- Strife, dislocation and genocide in the Darfur

region of Sudan;

- “Terrorist” events surrounding September 11th,

2001 in the USA;

- “Terrorist” school hostage events in September

2004 in Beslan, North Ossetia-Alania (Russian Federation);

- Natural disasters in southeast Asia after a

large December 2004 tsunami;

- Flooding, dislocations and property losses

associated with Hurricane Katrina in August 2005;

- Homelessness;

- School massacres at Bath Consolidated School in

1927, Virginia Tech University in 2007, University of Texas (Austin) in

1966, Columbine High School in 1999, and Jokela High School (Tuusula,

Finland) in 2007.

Even during the 4th

International Conference on Humanistic and Transpersonal Psychologies

and Psychotherapies, strife and violence among monks and the military in

Myanmar are a

replay of the violent 1988 clashes between students and the military in Burma.

More recently,

wild firestorms in southern California traumatized many persons after more than

2300 homes

and structures were burned to the ground and more than 500,000 persons had to

be evacuated.

Thus, if instances of war and trauma contribute to divergences in common sense

in individuals

and groups/herds, then studying processes and dynamics underlying experiences,

belief

formation, reality, and awareness may have value – especially if they have

profound

psychological, social, political and moral implications requiring universal

caveats emptor (Smith,

1986; Smith, 1987; Smith, 1992).

[14]

The extremely hard problem discussed in this report is not

associated with separate general

cultural experiences per se. For example, divergent differences in

common sense in Germans,

8 Examples include: “Parable

of the Old Men and the Young”; “The Dead-Beat”; “Mental Cases”; “Arms and the

Boy”; and “Conscious.”

Copyright © 2007 by Roulette William Smith, Ph.D. – All rights reserved.

Jewish Holocaust

survivors residing in the USA, or Jewish Holocaust survivors residing in Israel

per se are not considered. Rather, an immediate challenge concerns

separate realities among a unique and very small sample of German

persons9 who lack common sense (cf. Smith, 1986; Smith, 1987; Smith,

1988). Their common sense (or absence in common sense) does not comport with

mainstream common sense in Germany. The present in situ10

phenomenological study examines theoretical, philosophical (including moral and

ethical), methodological, economic, developmental, epidemiological and clinical

issues associated with this small sample of unknowingly needy and worried well

persons.

[15] Insofar as

‘common’ sense in humans develops between birth and approximately age six years

old (Smith, 1988; cf. Fulghum, 1986/2004), the extremely hard problem

specifically includes concerns for the extremely difficult scholarly and

clinical challenges of nurturing common sense skills in pre-school and

elementary school aged children who lack common sense. Because the propositi

and co-researchers in this study are adults, the focus is expanded to include

high school students, post-baccalaureate young adults, and older adults – none

of whom may have common sense.11 Older adults who lack common sense

may provide clues to boundaries and limitations regarding the intractability of

possible clinical treatments and therapeutic responses. Older adults also may

shed light on the long-term stability of common sense. A central theme guiding

this research is whether one can help these unknowingly needy persons. Is

providing assistance and nurturing change a lost cause? If DNA plasticity is

affirmed based on a hypothesis that DNA is the repository of long-term memories

(Smith, 1979; Smith, 2003b; cf. Exhibit 1), what combination of molecular,

psychopharmacological and/or therapeutic approaches can optimize therapeutic

responses, if at all – and at what ages?

[16] On a broader

scale, one is reminded that war often is a target and object of

many (military, political, game-theoretic and other) decisions and studies.

Research on common sense and aberrant common sense suggests that stability in

common sense may be a concrete benefit of peace. Examples of war and traumatic

situations possibly contributing to divergences in common sense were cited

earlier. The potential for homogeneity in common sense and possible

reduction in the prevalence of instances of aberrant common sense could be

one benefit and objective. Other possible benefits include reductions in costs

associated with clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic activities, as well as

societal costs associated with unforeseeable consequences of divergences in

common sense – including many of the types of traumatic events cited above. In

other words, micro- and macro-economic aspects of common sense must be factored

into the extremely hard problem, particularly insofar as rational thinking and

behaviors become economic issues. An apt analogy might be Ignaz Semmelweis’

observations about hospital sanitation when coupled with recent concerns about

methicillin-resistant (or, more accurately, multi-resistant) staphylococcus

aureus (MRSA; cf. Klevens et al., 2007). War and trauma may contribute to

messy, unhealthy and costly multi-resistant divergences in common

9 That the propositi in this

study are Germans may be purely coincidental – an accident of circumstances.

Retrospective analyses of other persons lacking common sense from the larger

database affirm many of the findings in this report. 10 The term in

situ is derived from Latin and means “in the situation.” 11

Throughout this report, we use aberrant common sense, having no common sense,

and lacking common sense interchangeably. Again, we are challenged to find

appropriate nomenclature which is sufficiently descriptive of underlying

cognitive processes. In alleging that persons have no common sense, there is no

intent to imply that those persons have no sense. Quite to the contrary, they

merely lack an appreciation for others’ sense within their herd, clan or

culture, and how their own behaviors do not comport with others’ common

or communal sense.

Copyright © 2007 by

Roulette William Smith, Ph.D. – All rights reserved.

sense – including

further aberrations in common sense and possibly leading to additional war and

“terrorism.” The hidden micro- and macro-psychological and economic costs

associated with chaos, war, terrorism, trauma, and stress-related disorders

must take front and center stage.

[17] At an

epistemological level, this report indirectly examines consequences of

professional failures to elucidate and explicate clinical aspects of

negativism, common sense, unknowing neediness and worried wellness in clinical

psychology, psychiatry, medicine, the neurosciences, and clinical social work.

Insofar as negativism and aberrant common sense often are manifested as chaotic

thinking and behaviors, occasional costly and harmful consequences, and in

other forms of inappropriate and complex human dynamics, the absence of a

negative personality disorder (cf. Millon, 1981) and aberrant common sense in

the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) IV-R TR

and various versions of the International Statistical Classification of

Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) – 9 and 10 now must be

redressed. The term “common sense” does not appear in the DSM IV-R TR, any

version of the ICD, or in any known clinical or professional textbook in

medicine, clinical psychology, or clinical social work.12 Yet,

disorders of negativism and common sense pose special challenges because they

mimic personality psychopathology as well as sociopathology due to their impact

on and consequences for others. Moreover, professional trends in most health,

health care and public health systems require that clients seek professional

assistance rather than professionals seeking out the unknowingly needy.

Unknowing neediness simply is not on the professional ‘radar’ – and especially

in disorders of common sense. Persons who lack common sense generally do not

seek help and require novel interventions. Worried wellness usually falls

within the purview of health insurers largely because of economic

considerations. There is little consideration for experiential aspects within a

client’s reality, within professional realities, or within the intersection of

those realities.

[18] In summary, a

truly difficult problem for consciousness research is brought to light in

studies of common sense and aberrant common sense. This problem becomes even

more complex when consciousness issues underlying experimenter-subject and

clinician-client dyads become a part of the challenge. Assessments of awareness

and need then become a central part of the equation.

Introduction

[19] When

Professors Cyrus and Magdalena Lee issued their call for papers for the 4th

International Conference on Humanistic and Transpersonal Psychologies and

Psychotherapies, the plan was to submit a manuscript discussing recent and

preliminary results on divergences in “common sense” obtained during the past

two years. A two month retreat in Germany was organized with a goal to assemble

and analyze data related to post-World War II divergences in common sense in

Germans, and Jewish Holocaust survivors in the USA and Israel. Insofar as a previous

12 Although many features of

aberrant common sense mimic the borderline personality, it is sufficiently

different and deserves its own Axis II designation. The ICD-10 does include two

classifications (that is, F94.8 – Other childhood disorders of social

functioning; and, F94.9 – Childhood disorder of social functioning,

unspecified) which could subsume some commonsense-related issues, although

those categories do not take into account adult-related matters. Those

classifications also do not capture the cognitive aspects of the putative

disorder. General anxiety disorders in adults (ICD-10 – F41.1; ICD-9

– 300.02) also are presenting symptoms in aberrant common sense, yet these

disorders fail to characterize the spectrum of findings.

Copyright © 2007 by

Roulette William Smith, Ph.D. – All rights reserved.

presentation at the

3rd International Conference on Humanistic and Transpersonal

Psychologies and Psychotherapies dealt with new perspectives on evolution

and their implications for nurturance and the transpersonal

(Smith, 2005), a goal this year was to show, at least theoretically, that

“common sense” and its divergences have a biological basis in humans consistent

with the far-reaching “tripartite” (that is, three part) theory of evolution. A

working hypothesis is that common sense generally is encoded in non-proteomic

regions of the DNA genome. It is nurtured between the time of birth and roughly

age six, and is not genetic per se. To the extent that common sense may

represent herd behavior, a reasonable goal is to determine if there are common

encodings for common sense within herds, cultures, etc. Just as a ‘genetic

code’ facilitates consistent protein production based on genes in the proteome,

a common non-proteomic encoding scheme may underlie long-term memory

mechanisms. Ultimately, changing Guanine*Cytosine::Adenine*Thymine13

ratios in selected regions of brain might serve as crude markers for assessing

common sense traits and components. These crude markers could lead to the first

serious efforts aimed at distinguishing common and unique consequences of

nurturance – and consciousness. This long-term research approach also can

demonstrate breadth, depth and richness in the tripartite theory of evolution.

That is, the theory is sufficiently powerful to capture and explain some of the

most elemental forms of the human experiences – and even at a molecular level.

[20] Common sense

is one of those elemental experiences. Most persons use the term common sense

in their everyday lives, yet as noted above, there are very few discussions of

the psychology of common sense in the literature. Despite its use, without an operational

definition, one may never truly “know” what is meant by the term common sense

within any herd or cultural context. Even when persons are asked to define

common sense, they often encounter considerable difficulties. Indeed, initial

interest in German common sense (in contrast to common sense in Germany) arose

in the late-1980s in conversations with friends and professional colleagues in

Munich, Germany. When discussing then extant research on common sense in young

children (Smith, 1986; Smith, 1987; Smith, 1988), there was no uniform

agreement regarding an appropriate German term for common sense. There was

general agreement that gesundermenschenverstand best represents the

notion of common sense. Moreover, because there is general agreement that Gezond

verstand is the Dutch expression for common sense and because of

similarities in Dutch and German languages, it is reasonable to assume that gesundermenschenverstand

is an appropriate representation of what generally is regarded as common sense.

Table 1 lists many representations of the term common sense in different

languages.

[21] The challenge

of understanding common sense is far more complex than one of determining

definitions or common terminologies (cf. Table 1). Psychotherapist Salamin

Alphonse (at the 4th International Conference on

Humanistic and Transpersonal Psychologies and Psychotherapies, personal

communication) notes that while bon sens may represent a correct

dictionary translation of the term into French, sens commun or sens

pratique may be more appropriate. The French term sens pratique (cf.

Bourdieu, 1998; Geertz, 1983; Robinson, 1983)14 may provide a clue

to an essential element in common sense; to wit, the importance of some

13 Hereafter designated G*C::A*T.

14 Clifford Geertz defines common sense as a form of ‘local

knowledge’ (Geertz, 1983); to wit, cultural language that forms the basis for

all agreements and is implied but not necessarily written. His emphasis is on

knowledge not underlying cognitive processes. Pierre Bourdieu (cf. <http://en.wikipediai.org/wiki/Pierre_Bourdieu> and <http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_Bourdieu>) defines sens

pratique in terms of fields, habitus and doxa.

Copyright © 2007 by

Roulette William Smith, Ph.D. – All rights reserved.

underlying

practical and socially conforming cognitive (memory and mental

processing) activities within groups, herds and/or cultures.15

This would support occasional claims that a person is “book smart,” yet has no

common sense.

[22] Table 1

provides a clue to another important aspect of common sense. The traditional

Chinese idiographic characters and Sanskrit terms for common sense point to

possible long-term and evolutionary aspects underlying common sense. These

representations underscore the importance of distinguishing and disambiguating nature

and nurture in discussions of common sense. Although many scholarly

pronouncements on common sense by western philosophers and religious scholars

may have originated in medicine during Middle Ages and Renaissance (Mullooly,

2003; Mullooly, 2006), the Chinese and Indian linguistic traditions clearly

indicate much earlier uses of the concept / notion. There also is evidence of

Aboriginal persons in Australia having historical and cultural notions of

common sense.16 Furthermore, when the naturalistic report of a

battle between a herd water buffalo and pride of lions is considered

(Schlosberg and Budzinski, 2004), it is evident that both biological (that is,

nature) and herd / cultural (that is, nurturance, development and adaptation)

components are important.

A Role for Evolution in Common Sense and A Role for

Common Sense in Evolution

[23] A tripartite

theory of evolution (Smith, 2005b; Smith, 2006a; Smith, 2006a; Smith, in

preparation) differs from Charles Darwin’s theory insofar as the tripartite

theory has three unique components. The first component (A) subsumes all

of Charles Darwin’s ideas. In other words, Darwin’s theory is necessary,

though not sufficient, to explain human evolution. The two remaining components

in the tripartite theory are: B) in utero experiences and

possible consequences in later life related to those in utero

experiences (that is, intrauterine events and “experiences” between mother and

child taking place in a woman’s womb during pregnancy; possible transfers of

‘soulful’ and nurturing information in utero, and, possible long-term

consequences of drugs, addictions, methylations/imprinting and the intrauterine

environment; cf. Verny and Kelly, 1981/1983; Barker et al., 1989; cf. Coles,

1990; Haig, 1996; Forsen et al., 2000; Killian et al., 2000; Barker, 2001;

Godfrey and Barker, 2001; Eriksson et al., 2001; Reik and Walter, 2001; Verny

and Weintraub, 2002; Barker, 2002; Barker, 2003a; Barker, 2003b; Bihl, 2003;

DiPietro, 2006; Dolinoy, Huang and Jirtle, 2007); and, C) DNA is the

repository of long-term memories in brain and the immune system (Smith, 1979;

see Exhibit 1). An abundance of clinical, epidemiological, experimental and

theoretical evidence suggests that changes in DNA occur dynamically largely in

non-proteomic regions of the genome (Smith, in preparation). Preliminary

evidence from a variety of sources suggests that many of those DNA changes in

brain may convert adenine*thymine-rich regions to guanine*cytosine-richer

regions, possibly accompanied by methylation events. In immune memories,

recombinations and rearrangements in immunoglobulin hypervariable genes

represent an established mechanism (Tonegawa et al., 1978; Sakano et al.,

1979).

[24]

15 I especially am grateful to

Jutta Thompson, Greg Andonian, Gerard De Zeeuw, Salamin Alphonse, Fei Zi, Ming

Lee, John Clemens, Julio Vidaurrazaga, Byron Marshall, James Stasheff, Michael

Eisenstadt and others for assisting me in sorting out the importance of various

cognitive components underlying common sense and aberrant common sense. These

components include memory, culture / herd, processing, problem-solving,

mistakes and error processing, etc. 16 At this time, it is not known

if any Aboriginal notions of common sense are consistent with ‘dream time’.

Copyright © 2007 by

Roulette William Smith, Ph.D. – All rights reserved.

Other memory

mechanisms associated with C include mutable loci and transpositions

(McClintock, 1950; Smith, 1979), mirror neuron activities (e.g., imitation and

grasping of intentions; di Pellegrino et al., 1992; Fadiga et al., 1995;

Rizzolati et al., 1996a; Rizzolati et al., 1996b; Gallese et al., 1996; Grafton

et al., 1999; Iacoboni et al., 1999; Arbib et al., 2000; Ramachandran, 2000;

Iacoboni et al., 2001; Iacoboni et al., 2005), and psychovirus actions (Smith,

1987; Smith, 1988; Smith, 1992). In addition, new transmissible and epigenetic

memory mechanisms (e.g., autotoxicity, autovirulence, context-specificity,

‘hit-and-run’ and ‘beneath-theradar’ transmissible infections; Smith, 1983;

Smith, 1984; Smith, 2003a) may contribute to autoimmune, psychosomatic and

other psycho-immuno-neurological axis disorders and syndromes.

[25] What generally

distinguishes A from B and C is the forms of information

transmitted and how that information is reproduced and replicated. The

replication and transmission of molecular information associated with A

primarily is genetic. Although Darwinian evolution presumably can accommodate

the transmission of substituent particles (for example, prions and other

autotoxins; transposons, microRNAs, snRNPs, and other autovirions; and other

potential generators of diversity [Smith, 1984; Smith, 1989]), psychoviruses

and mirror neuron actions (e.g., imitation and grasping of intentions) are more

difficult to reconcile. Components B and C generally cannot be

explained in Darwinian evolutionary terms. B and C can explain

Lamarckian evolution and more – including common sense. C identifies

other evolutionary advantages often overlooked in Darwinian evolution –

including aging and different economic benefits (e.g., volunteerism and

philanthropy). This tripartite evolutionary perspective may generalize to marsupial

mammals, too (cf. Killian et al., 2000). Marsupials include opossums in the

Earth’s northern and southern hemispheres, along with an extraordinary variety

of other marsupials mostly in the southern hemisphere (for example, kangaroos,

wallabies, koala bears, wombats, and even the Tasmanian devil and thylocine;

see <http://www.pbase.com/mr2c280/australia_mammals>).

[26] That there may

be a molecular basis for common sense and that there is a role for evolution in

common sense, is not at all obvious. Some scholars may be inclined view common

sense diachronously (that is, of, relating to, or dealing with phenomena

[as of language or culture] as they occur or change over a period of time

prospectively and/or cumulatively) or synchronously (that is, chronological

arrangement of historical events and personages so as to indicate coincidence

or coexistence; retrospectively and/or historically). These dichotomies,

dualities, oppositions and distinctions may be artificial and simplistic – and

represent instances of descriptive – structuralism and its inadequacies

(Smith, 1983). Descriptive-structuralism is unlikely to shed any light on a

possible molecular basis for common sense.

[27] A second

possible approach to explicating common sense might involve heuristic –

functionalism (Smith, 1983). One’s views of common sense must appreciate

diachronous and synchronous (i.e., descriptive) details. Yet, an underlying

appreciation for molecular and biological (i.e., functional) processes also is

in order. Those processes may provide clues to broad molecular elements,

even though those processes remain to be more fully explicated. As noted

earlier, common sense possibly is encoded in non-proteomic portions of the

genome. To the extent that this possibility is affirmed, an immediate challenge

and long-term goal may be to ascertain whether there really are “common”

elements underlying brain activities – and especially in regard to

consciousness and common sense. In other words, does the term “common” in

common sense have relevance at a molecular and non-proteomic level?

[28] This report

reveals a third possible approach to explicating common sense. After planning a

two month scholarly retreat in Germany in order to complete a report for the 4th

International Conference on Humanistic and Transpersonal Psychologies

and Psychotherapies, those best laid plans were derailed because of

emergent chaos in the German household. The planned report not only would

provide preliminary evidence of three divergent strands in common sense emerging

from post-World War II, the report would have considered biological,

evolutionary and developmental advantages of common sense to survivors of World

War II. In the end, aberrant common sense was determined to be the source of

the chaos. This third approach emerged from that chaos. In situ

observations of aberrant commonsense17 behaviors were

extraordinarily rich, informative and invaluable, and, represent a unique and

fortuitous embodiment of logistic reasoning (Smith, 1983). By viewing

aberrant common sense in real-time, one now may be able to understand more

about both common sense and aberrant common sense.

[29] In summary,

preliminary findings related to the evolution of common sense in generations of

post-World War II Germans and Holocaust survivors, when coupled with logistic

reasoning about aberrant common sense, possibly can provide a glimpse into

biological, developmental and evolutionary mechanisms underlying common sense

and aberrant common sense. These findings also will support using common sense

as a concrete marker when building a solid foundation in peace studies.

Finally, the findings now propel the ‘transpersonal realm’ into virgin and

uncharted territories in genomic studies and neurosciences.

[30] Logistic

reasoning also provides clues to needs for proactive and anticipatory

strategies aimed at avoiding divergences in common sense. For example,

increasing numbers of mothers now serve in the USA military services. This

phenomenon also is occurring in other nations. Estimates of USA women soldiers

serving in the Iraq war now exceed 170,000 tours in duty. Women also comprise

approximately 10% of soldiers assigned to the war in Iraq (<http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=14964676>; Norris, 2007). Women

in the USA military services also have higher prevalence rates of

post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) than their male counterparts (Norris and

Hillard, 2007; Milliken, Auchterlonie and Hoge, 2007). Having women serve in

the military is deemed a social objective aimed at reducing gender inequities

and providing human rights consistent with the United States Constitution. Yet,

many of those military mothers are being separated from their young children

during those children’s formative years when common sense is developing. Those

children also could be exposed to psychoviruses or other situational stresses

from other non-parental and non-familial sources.

[31] Military

service women of childbearing ages, and who may have experienced PTSD, pose a

second challenge. Their PTSD could lead to aberrant nurturance of any offspring

subsequent to their diagnosis of PTSD, thereby causing other divergences in

common sense. Ultimately, an increase in prevalence rates of aberrant common

sense may be a consequence of the shortsightedness in USA military strategies

regarding the lack of strategic planning for long-term

17 Throughout this report,

common sense is used as a noun, and commonsense is used as an adjective.

Copyright © 2007 by Roulette William Smith, Ph.D. – All rights reserved.

consequences of

childbearing women in the military (cf. Montagne, 2007; Norris, 2007; Milliken,

Auchterlonie and Hoge, 2007; also see <http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=14964676>). Any aberrations in

common sense may be viewed as concrete markers and indicators of the

ill-thought and ill-advised prosecution of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Even more important, the national caveats emptor in regard to “terrorism” are

profound (cf. Smith, 1987; Smith, 1988; Smith, 1992; Smith, 2002). Insofar as

these wars allegedly are responses to terrorism, evidence of excessive

humiliation and torture (at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, CIA extraordinary

rendition sites worldwide, and the US detention facility at Guantanamo Bay,

Cuba), terrorism could beget further torture and terrorism – contributing to a

cycle of divergent, divergences in common sense. Similar cycles of terrorism

are evident in Russia where Chechnyan terrorists become even more emboldened by

Russian responses to Chechnyan terrorist attacks.

[32]

This proactive scenario should cause one to pause and consider what clinicians,

scholars,

transpersonalists, military planners and others should recommend and practice

if peace,

common sense and sanity are to be preserved – and if one’s offspring (and

others) are to enjoy

long-term benefits of peace. There also is a need for concrete

technologies (in terms of reliability

and validity) to assess common sense and its aberrations – and, by inference,

peace. It now is

time to invent and develop non-invasive technologies to assess DNA changes –

and to correlate

DNA dynamics with common sense, peace and other clinical entities.

[33]

Parenthetically, in citing the proactive consequences of the war on future

manifestations of

common sense in the USA and elsewhere, it also is worth mentioning a

little-noted proactive

aspect and consequence of China’s ‘one child” policies on population control.

There is little

evidence that the forefathers of this policy weighed its consequences and

implications for the

spread of HIV/AIDS. This example is particularly important because of a

question from a young

female university student at the 25 September 2007 “Going Along with Professors

– Speakers of

the World” Forum at the International Hall in one of university of Guangzhou’s

10-university

center complex. The event was co-hosted by the Guangzhou University of Chinese

Medicine.

The woman requested professors’ views on “one-night (sexual) stands” (cf.

Wilson, 2007).

[34]

The young woman’s question was extraordinarily important insofar as the spread

of HIV in

university communities can have devastating long-term consequences. Her

question also was

important because of the relative imbalance in the ratio of males to females

caused by China’s

one-child policy. The transmission of other sexually transmissible diseases is

no less important

(cf. Moss et al., 2007). Most persons overlook one extremely important

epidemiologic fact about

HIV, lentiviruses (in general), and other transmissible agents causing slowly

progressive

diseases (for example, prions). In all instances, the quantity of the virus is

inversely correlated

with the profoundness of disease within an individual and within the herd

(Smith, 1984; Smith,

1994; Smith, 2001; cf. Kelley et al., 2007). As virus titers increase (that is,

as virus “load”

increases), then incubation periods become shorter. Over the long-term, as

virus titers increase,

manifestations of diseases become more profound. This finding has special

significance in

physical islands and social islands because virus titers sometimes can increase

exponentially –

both within individuals and herds. Perhaps more important, all agents causing

slowly

progressive processes comport with as many as eleven ‘near-axiomatic’

features – including the

inverse proportionality rule and an ‘island’ hypothesis (Smith, 1994).

[35] The ‘island’

hypothesis states that prevalence rates for infectious agents causing slowly

progressive diseases and the profoundness of those associated diseases generally

are greater in island environments. College campuses often are social islands

with many unknowingly needy clients (cf. Wilson, 2007). These factors, taken

together, reveal increased risks for women in China (that is, a social island

confounded by the one-child policy) to receive higher titers of HIV than their

male counterparts – at least initially. To the extent that there are fewer

female sexual partners available in the society, increased titers and

infections rates then can shift to males. Hence, if sexual activities are

carried out without consideration for others, the prevalence of HIV and

opportunistic infections could continue to rise exponentially – and

dynamically, shifting disproportionately among females and males. In short,

common sense, common knowledge, and evolutionary considerations dictate

that human sexual predilections take into account HIV/AIDS, other sexually

transmitted diseases, and socio-politico dynamics. By this logic, “one night”

stands, at this time in history, may be regarded as a form of aberrant common

sense.

[36] Overall, the

spread of HIV in humans is nicely illustrated in the Benetton photo

essay appended near the end of this paper (Exhibit 2). The particular issue of

the Benetton Colors Magazine appeared in 2000 – just in time for the XIII

International AIDS Conference in Durham, South Africa. At that time, the

spread of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa was thought to represent the worse

case scenario in this dread pandemic. The alarming changing prevalence rates of

HIV/AIDS in India and China now should give pause to all Chinese nationals –

and especially to university and college students (cf. Wilson, 2007). Along

with the spread of HIV/AIDS, one can anticipate an increase in the prevalence

rates and varieties of other infectious diseases – and especially sexually

transmitted diseases.

[37] Before leaving

the issue of HIV/AIDS, it is important to stress the underlying common sense and

common knowledge implications (see Footnote 46). Knowledge about HIV/AIDS,

other sexually transmitted diseases, and opportunistic pathogens must become

common knowledge, in addition to the common sense issues regarding

transmissibility of infectious pathogens. Cooperation is a central tenet in

common sense. This is in contrast to reasoning used by virtually all persons

with aberrant common sense. All other things being equal, the ways and actions

of persons who lack common sense focus solely on their own ways and actions –

and not the ways and actions of the herd. The last two graphics in this report

are taken from an elementary school morality education textbook entitled “SHOGAKU

DŌU TŌKU/どうとく(Morality /

The way of virtue) for 1st, 2nd, and 3rd

grades” (Umiuchi et al., circa 1967; Exhibit 4). They are excellent

illustrations of both cooperation and common sense.18 Similar crisp

and clear, “commonsense” instructions about cooperation and considerations

for others were provided as animated passenger information on Japan

Airlines (JAL) flights to the 4th International Conference

on Humanistic and Transpersonal Psychologies and Psychotherapies. Another

commonsense example from recent Japanese literature is Moriko Shinju’s Mottainai

Grandma comic series illustrating the inappropriateness of waste (Shinju,

2004/2004; Kestenbaum, 2007). Shinju’s underlying message is the common adage

“waste not; want not.”

18 Unique in the second lesson

is the exceptional step (the last panel on the bottom left) taken by the fox

character to teach others what it (that is, the fox) learned from the bear.

This step generally is not seen in lesson plans in schools in the USA. The

example also illustrates cultural differences in common sense.

Copyright © 2007 by

Roulette William Smith, Ph.D. – All rights reserved.

An In Situ Phenomenological Analysis of

Aberrant Common Sense

[38] As mentioned

earlier, a two month scholarly retreat was planned to complete a manuscript for

this 4th International Conference on Humanistic and

Transpersonal Psychologies and Psychotherapies. Those plans were disrupted

for elusive reasons which remain difficult to fully understand. During the

retreat in Germany, glaring, costly and potentially harmful examples of

aberrant common sense were continually encountered. The remainder of this

presentation focuses on an in situ phenomenological study19 and

analysis of aberrant common sense during that two month period. The situation

was particularly interesting because of the confluence in emerging concerns for

“illness,” “aberrancy,” “health,” “wellness” and “helping.” Regarding helping,

the focus in this in situ study is on unknowing neediness (in persons

lacking common sense), and not the worried well. This is not to conclude that

persons lacking common sense cannot be among the worried well. Indeed,

Proposita “D” (see below) often presents as a hopelessly worried well client.20

Propositi –

co-researchers in this study21

[39]

The propositi in this report include a divorced middle-aged mother (Proposita

“A”) and her two

young adult, interracial22 daughters Propositi “B” and “C”. The

investigator has known Proposita

“A” since July 2004. He met Propositi “B” and “C” in March 2005. Other

propositi include two

somewhat elderly next door neighbors (Proposita “Y” and Proposita “Z”) whom the

he also met

in March 2005. Propositi “Y” and “Z” are unrelated.

[40]

Of these propositi, Proposita “C” clearly lacks common sense. This was

immediately apparent in

March 2005. Aberrant common sense in Propositi “Y” and “Z” became evident in

2006. Their

aberrancies in common sense are somewhat peripheral to the present study,

except insofar as

their behaviors initially sparked concerns about potentially high prevalence

rates of aberrant

common sense in post-World War II Germany. Propositi “A,” “B,” “C,” “Y,” and

“Z” are German

citizens residing in a large urban city in Germany. Proposita “A” was diagnosed

with aberrant

common sense in May 2007 midway through this in situ study. There is no

evidence that

Proposita “B” has any aberration in common sense, although indirect evidence

suggests that her

father Propositus “X” lacks common sense.

[41]

A divorced middle-aged mother (Proposita “D”) is known to this investigator

since 1972. Her

aberrant common sense was diagnosed in 1985 – shortly after it was reported

that transmissible

negativism and aberrant common sense represent important clinical entities.

Prior to 1985,

19 Phenomenological studies in

psychology and other social sciences are not new (cf. Braud and Anderson,

1998). This study is unique insofar as its in situ component is more

akin to ethnographic research in anthropology. 20 Interest in the

unknowingly needy and worried well is derived from the classic adage / paradigm

about the dichotomization of knowledge and action (see Endnote after the

References). 21 The word “propositi” is the plural of proposita

(female) and/or propositus (male). These terms refer to designated

persons in a pedigree or family tree. 22 Interracial, interfaith and

interethnic relationships are cited because of past findings associated with

propositi who lack common sense (Smith, 1992; Smith, 2004c). Of 37 propositi

marriages and divorces, 24 of those marriages were interracial and 1 was an

interfaith marriage (67.6%). Also, of those 37 propositi marriages, 16 involved

2nd marriages (43.2%), and 1 involved a 3rd marriages

(2.7%). Twelve of these multiple marriages were to interracial partners. Thus,

the significance of the high prevalence rates of interracial, interfaith, and

interethnic relationships among persons with aberrant common sense remains to

be explored beyond being a mere caveat emptor. More than 70% of Proposita “A’s”

partners are interracial.

Copyright © 2007 by

Roulette William Smith, Ph.D. – All rights reserved.

Proposita “D” was

considered to be strange, challenging, difficult, moody, emotionally labile,

worried well, anxiety-laden, frequently prone to errors and misunderstandings,

unreliable, and self-absorbed. In this study, Proposita “D” is one case control

for Proposita “A” insofar as her age is the same age as Proposita “A,” she and

Proposita “A” are second generation survivors of World War II, and Proposita

“D” has members of her family who were displaced by World War II. Proposita “D”

has a teenage, interfaith/interethnic son (Propositus “E”) who is approximately

five years younger than Proposita “C.” Propositus “E” is selected as a case

control for Proposita “C” particularly in view of findings on psychoviruses

(Smith, 1987; Smith, 1988; Smith, 1992; Smith, 2004c) and higher prevalence

rates associated with anxiety disorders in families. The significance of the

latter will become apparent later in this report.

[42] Both Propositi

“D” and “E” are cited in earlier studies (Smith, 1988; Smith, 2004b; Smith,

2004c; Smith, 2006a; Smith, 2006b; Smith, 2007a; Smith, 2007b). Proposita “D”

is Jewish and, as noted, a second generation survivor of World War II. Her

father’s family is Sephardic Jewish, although he was born in Poland and

migrated to Canada before the Holocaust. Her mother is Ashkenazi Jewish who,

along with her (mother’s) sister, was hidden by French Catholic families on

farms in France. They were raised as Catholics. Propositi “A” is a non-Jewish

second generation World War II survivor, and Propositi “Z” and “Y” are first

generation World War II survivors whose religious heritages are unknown.

[43] By any description,

Propositi “C” and “E” would be regarded as non-autistic savants insofar as each

excels in some personal passion (that is, Proposita “C” is a child actress of

considerable acclaim, and Propositus “E” is an expert on Civil War history).

Propositus “E” alleges pass-life experiences and past-life regressions, though

this has never been assessed.

[44] Proposita “F”

is a second case control for Propositi “A” and “D.” She is a divorced

Japanese-American who lived her formative years in internment centers in

California (that is, from months shortly after her birth until the closure of

the internment centers). Thus, Proposita “F” may provide another perspective on

the impact and consequences of World War II on the development of common sense

and it aberrations.

[45] Of all

propositi, only Proposita “D” actively discusses World War II – a common

finding in Jewish Holocaust survivors and their offspring. Germans and

Japanese-American survivors of World War II and their offspring are less likely

to openly discuss war-time experiences.23 Indeed, it is somewhat

difficult to document Trümmerfrauen (that is, “rubble women”)24

activities in Germany, even though they played a significant role in the

reconstruction of select regions in Germany (because of the scarcity of males

due to deaths and infirmity caused by World War II). The

23 Different groups respond

differently to war and trauma. Armenians are increasingly vocal about their

1915 experiences. Cambodians are relatively mute regarding the “killing fields”

and displacements. Chinese only recently have begun to discuss the Cultural

Revolution. Thus, an analysis of rhetoric (including prose, poetry, art, film

and music) and divergences in common sense may have value if divergences in

common sense in responses to war and trauma are affirmed. 24 Because

their activities generally were not organized or coordinated, Trümmerfrauen could

be extremely important in one’s quest to understand the evolution and

development of common sense and aberrant common sense in post-World War II

Germans. However, there is no evidence that Propositi “A,” “B” and “C” are

progeny of Trümmerfrauen.

Copyright © 2007 by

Roulette William Smith, Ph.D. – All rights reserved.

investigator knows

relatively little about Propositi “Y” and “Z,” however they may be significant

in future studies because they are first generation survivors.

[46] Of more than

50 adult propositi in a database of aberrant common sense (Smith, 1987; Smith,

1992; Smith, 2004c), there is very little evidence of significant religious or

spiritual practices among the propositi. None of the in situ propositi

revealed any spiritual practice, even though Propositi “A,” “B” and “C” are

Roman Catholic. Propositi “A” refused to pray in two situations where prayer

may have been appropriate or indicated. This general observation could provide

an opportunity for further investigation, particularly in the context of

resistance, intransigence and “my way or the highway” responses in most persons

lacking common sense. Faith in higher powers, in contrast to hope from the

occult, lies at the core of this concern.

Mitigating

circumstances may have contributed to the emergence of evidence of aberrant

common sense in Proposita “A”

[47]

Proposita “A” is the master tenant in a house owned by the investigator, as is

her daughter

Proposita “C” A third unrelated young adult male (Propositus “W”) also resides

in the household.

Proposita “B” is the first-born child of Proposita “A,” and is a university

student living

approximately one hour away from her mother and sister.

[48]

As reported earlier, there were advance plans for a two month scholarly

retreat. These plans

were negotiated with Proposita “A” at least six months prior to the planned

visit. Despite this

agreement, Proposita “A” may have changed her mind, although this was never

communicated

to the investigator.25 Because of egregious, profound and ongoing

instances of extreme passive-

aggression in Proposita “A” upon his arrival in Germany, the focus of this

research was changed

to identify and understand possible reasons underlying those aberrant

behaviors.

[49]

The diagnosis of aberrant common sense in Proposita “A” was made on 20 May 2007

after

more than one and a half months of observations,26 visits with

relatives, family, friends and other

acquaintances, and, direct observations of breakages, mistakes,

misunderstanding, and

numerous inappropriate actions. The thoroughness of this investigation was

deemed essential

because Proposita “A” revealed no obvious aberrancies in common sense in the

past, and

because of the sanctity of the business (that is, landlord – tenant)

relationship.

[50]

The concept of passive-aggression was unknown to any propositi in this study.

Despite this,

Proposita “C” and her father (Propositus “X,” the ex-spouse of Proposita “A”)

are profoundly

passive-aggressive.27 This was observed in March 2005, during visits

in 2006, and also was

25 This is just one example of

Proposita “A’s” extreme passive-aggression. 26 The chaos at the

beginning of the in situ period was palpable. It then was necessary to

“rule out” borderline personality disorder, confabulations, severe

passive-aggression without other co-morbid disorders, etc. 27 This

finding raised two vexing issues. The first vexing issue concerns the earliest

manifestations of passive-aggression in Propositi “A,” “C” and “X.” This was

important in disambiguating possible vectorial actions of psychoviruses – ‘from

whom to whom’. The second vexing issue was whether aberrant common sense in

Propositi “A” and “X” may have been transferred to each other. After in situ

encounters with Proposita “A’s” mother, siblings and childhood friends, it was

apparent that Proposita “A” lacked common sense prior to meeting Propositus

“X.”

reported by

Proposita “A” in numerous telephone calls and on various occasions. The

father-daughter passive-aggression was so profound and frequent that it often

produced stress and anxiety in Proposita “A.” During the April-May retreat

period, Proposita “B” also cited evidence of her father’s profound

passive-aggression. Direct and indirect evidence, as well as testimony from

friends, confirmed that Propositus “X” lacks common sense.28

[51] During the

retreat period, aberrant common sense associated with Proposita “A,” and

secondarily with daughter Proposita “C,” contributed to chaos,

misunderstandings, property destruction, harmful and destructive personal and

social relations, and faltering landlord-tenant relationships. The purpose of

the present in situ phenomenological analysis is to document and

understand aberrations in common sense during the two month period. A goal is

to identify processes associated with aberrations in common sense, and reasons

for their destructive consequences. More important, because of ongoing interest

in the evolution and development of common sense in generations of Germans and

Holocaust survivors in post-World War II Germany, it was deemed important to

understand the etiology of aberrant common sense in situ. After all, it

also is important to understand and possibly rule-out any relationship of the

immediate instances of aberrant common sense to the broader issue of

divergences in common sense arising from World War II. This is the reason

Propositi “D,” “E” and “F” are incorporated in the study as case controls.

Can persons

with aberrant common sense shed light on “healthy” or “balanced” persons’ (that

is, common) sense – gesundermenschenverstand?

[52] Quite often

diseases are used to elucidate and explicate normal processes. For example,

research on slow viruses which contribute to dementia in brain and the immune

system led to a new model of evolution and long-term memories (Smith, 1979).

That same model accurately anticipated HIV/AIDS (Smith, 1983; Smith, 1984) and

more than 90 epigenetic diseases associated with gamma herpesviruses and

adenoviruses (Smith, 2003a). Linus Pauling’s groundbreaking research on sickle

cell anemia led to an understanding of the molecular basis for genetic diseases

(Pauling et al., 1949). Huntington’s disease is likely to shed light on

boundaries between proteomic and non-proteomic regions of genomes, as well as

relationships among cognitive and sensory-motor components. Hence, an ambitious

goal in the present research on aberrant common sense is to provide useful

clues to reality, consciousness and formation of beliefs – in addition to a

possible biological basis for common sense.

[53] Ponder these

questions: how can one diagnose aberrant common sense? What distinguishes

common sense from aberrant common sense? What nomenclature should be used to

describe persons who lack common sense? Is “aberrant” an appropriate term to

describe one having no common sense? Can psychiatry, clinical psychology and

other “helping” professions develop an awareness of, appreciation for, and therapeutic

approaches to “transmissible negativism,” “aberrant common sense,” “unknowing

neediness” and “worried wellness”? Why have other scholars failed to recognize

diseases of common sense, unknowing neediness, and worried

This does not rule

out Propositus “X” lacking common sense early in his childhood. Indeed,

indirect and second-

hand information support this proposition.

28 Passive-aggression and aberrant common sense represent different

psychological entities. Earlier studies on

“transmissible negativism” led to a hypothesis that ‘transmissible negativism’

psychoviruses could contribute to

aberrant common sense, particularly in young children between birth and

approximately age 6 (Smith, 1987; Smith,

1988; Smith, 1992; Smith, 2004c). However, not all persons with aberrant common

sense are negative.

Copyright © 2007 by

Roulette William Smith, Ph.D. – All rights reserved.

wellness? Insofar

as persons who do not have common sense generally will not self-refer

themselves for therapy and counseling, how can chaos and other harmful

behaviors be circumvented in this unknowing needy subpopulation? Finally, why

is there an absence of any concept of common sense or aberrant common sense in

textbooks on psychiatry, clinical psychology and other helping professions –

worldwide? Have our heads been stuck in the sand during the past century?

Is there a

biological basis for common sense?

[54] Two years ago,

Smith (2005b) announced a tripartite model of evolution at the 3rd

International Conference on Humanistic and Transpersonal Psychologies and

Psychotherapies. A visual aid was used to depict that only 1.2% of the

human genome comprises the “proteome” – the protein encoding region of the

genome. That is, only 1.2% of the DNA in cells can explain our genes. Those genes

and proteins are the principal “stuff” in Darwinian evolution. For purposes of

simplification, one might call this nature. A large fraction (say, 75%)

of the remaining ~98% of the genome sometimes is referred to as “junk” DNA, and

cannot be explained by Darwinian principles. It now is proposed that a small

fraction of this allegedly “junk DNA” is used to encode “common sense” – beginning

at birth and extending to one becoming roughly six years old (cf. Fulghum,

1986/2004). An empirical issue then becomes whether the encoding schema for

common sense are consonant or “common” in any ways for animals in a cohort. If

so, this could provide powerful and compelling evidence that herd behavior may

have a common biological basis. The general proposal is that nurturance

and other forms of long-term memories largely are encoded in non-proteomic

portions of the genome. Because this presentation focuses on persons who do not

have common sense, a general theory of common sense will be discussed and amply

documented elsewhere (Smith, 2004a; Smith, 2004b; Smith, 2004c; Smith, 2007a;

Smith, 2007b; Smith, 2007c; Smith, 2007d). Suffice it to say, aberrant common

sense may be encoded somewhere in non-proteomic regions, but this no longer is

the primary concern.

[55] This report is

about people who do not have common sense. Smith’s earliest observations of the

phenomenon of aberrant common sense occurred in 1985 (Smith, 1986; Smith,

1988). Nine children in a Sunnyvale, California Elementary School Mathematics

Lab revealed types of mistakes in mathematics that simply could not be

explained using any form of error analyses. Their responses were outliers by

virtually every assessment of errors. More will be said about those 1985

experiences near the end of this report on in situ phenomenological

analyses and experiences of the situation in Germany earlier this year.

What is common

sense and why is it important?

[56] In earlier

reports (Smith, 2004c; Smith, 2006b; Smith, 2007a; Smith, 2007b; Smith, 2007c;

Smith, 2007d), common sense was defined as “core ‘nurturance’ in herds.”

Although this definition is vague, its intent was to underscore the uniqueness

of common sense in herd behaviors. Herds may include spiritual, ethnic,

cultural, sects, professional, or other groupings of living entities. In plain

language, the definition of common sense was meant to represent core

“nurturing” experiences possessed by most members of a herd. Nurturance

derives from parents, friends, community and other herd experiences – including

environmental influences. This is an embodiment of Marian Wright Edelman’s

reference to an African proverb that “it takes a village to raise a child.”

Aberrant common sense generally refers to outliers – both as individuals in the

herd and as thinking and problem-solving behaviors not shared by most members

of the herd. The village metaphor fails. Persons with aberrant common sense do

not seem to have acquired village or herd teachings / values. The vagueness in

the earlier definitions was meant to underscore uniqueness, variability and

value-laden aspects in taught, learned and nurtured experiences.

[57]

In the end, the present in situ phenomenological findings reveal that

neither of these definitions

– for common sense

or aberrant common sense – is adequate or sufficient to capture the salient

mental features central to logic and information processing in common sense. On

the surface,

nurturance should be both necessary and sufficient to enculturate all of the

needed logical skills

for survival and other practical decision-making. This in situ

phenomenological study reveals

otherwise. It underscores a need for a finer grained analysis of thinking,

cognition and

mentation. For example, earlier studies revealed the importance of mathematics

problem solving

and reading skills in commonsense and aberrant commonsense behaviors (Smith,

1987; Smith,

1988; Smith, 1992). Those studies also highlighted unusual error processes

associated

mathematics and reading in persons who lack common sense. For this study,

selected

mathematics, problem solving and deep reading skills are deficient in adult

Propositi “A,” “D,”

“F,” and younger propositi “C” and “E.” Their deficiencies teach that logistic

reasoning and

anticipatory skills are critically important in common sense, whereas the

absence of logistic

reasoning and anticipatory skills may be associated with frustration,

humiliation and anxiety

disorders. This may be a reason why Proposita “D” graduated cum laude from

University of

California, Berkeley and possess a law degree, yet still lack common sense.

Propositi “A,” “C,”

“D” and “F” are high-functioning, non-autistic individuals except when

confronted with extreme

tasks and/or critical thinking challenges. Then they become “unglued” and “come

apart.”

[58]

Perhaps more important, the scope of breakages, errors, mistakes,

misunderstandings and

misinterpretations are quite prevalent and prominent in persons lacking common

sense. Those

error processes often produce anxiety and generalized anxiety disorders over

extended periods

of time. Estimates of prevalence rates for anxiety disorders range from 3% -

17% in the general

population (Ries, 1996; Gater et al., 1998). Insofar as many of the propositi

in this study live

near Mainz, Germany and at a greater distance from Berlin, the prevalence rates

for generalized

anxiety disorders in Mainz are particularly intriguing (cf. Table 3 in Gater et

al., 1998). Yet,

because little is written about common sense, aberrant common sense and anxiety

disorders, it

is not known whether aberrant common sense is a major component of this

fraction.

[59]

In the present study, Proposita “A” is medicated for an anxiety disorder. She

revealed this to the

investigator and only one other person. None her children, siblings or other

family members

were informed of her medication. Proposita “D” resolutely refuses any medical

attention for her

frequent anxiety attacks – even upon recommendations of her primary care and

other

physicians. Proposita “C” is unmedicated, although she has consulted a clinical

psychotherapist

upon the recommendation of her primary care physician. Neither Propositi “A”

nor “C” is willing

to consider long-term psychotherapy (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy),

even with

substantial positive incentives and inducements.

[60]

Although many features characterize all propositi in this study (see Table 2),

two features of

aberrant common sense define all propositi in this study and propositi in the

larger database of

propositi with aberrant common sense. First, all propositi show limitations in

overall scope and

purview for broad issues (that is, they never are able to see the “big

picture”). Second, each of

the propositi

relies almost exclusively on her or his thinking – “it’s my way or the

highway.” Regarding the latter, there virtually is no evidence of “commonality”

in their common sense. Those personal limitations also may be sources of stress

and anxiety, especially when their reasoning skills fail them.

Is common sense

limited to humans?

[61] Please view

the video clip of predator-prey behavior (involving water buffalo, lions, and a